"Also, he must have foreseen, if dimly, that it was nothing less than martyrdom which lay in wait for him along the way; that this brand which Fate had set upon him was precisely his token of apartness from all the ordinary men of earth." — Confessions of a Mask

All men are rain barrels of their era — collecting the ideals of their family, their nation, their culture, their genetics. Before each man even has time to look around him and blink his entire psyche is filled with a million things, a million stories, a million separate wills all striving with intense passion to become dominant. How can one overcome such an existence?

It is a question one asks oneself again and again. How can one escape their circumstances of birth? The answer comes quietly. There is no escape, only transcendence. There is no way out – only through.

Yukio Mishima was born into what once had been a samurai family, now reduced to the status of commoners. He was raised as a girl by his overbearing grandmother – never allowed outdoors, never allowed to experience the world besides through a window. The wartime years of his youth instilled in him a love of death and night and blood — a love perhaps always there, but brought to light by his intimate experiences with the Japanese defeat in World War II. He was a small, weak and sickly as a child and remained so as a young adult. He was tormented by his own homosexuality and masochistic desires. He was consumed by the nihilism of his time, whether the active nihilism of the war years or the passive nihilism of the post war westernization. His whole disposition and the disposition of his era demanded oblivion. His unconscious was a black and sticky pit filled with monsters. In the beginning of Confessions of a Mask Mishima recounts various vaguely masochistic homosexual urges he has experienced throughout his childhood. It becomes clear to him that these will be the demons he must fight for all his life. Mishima writes:

"I had been handed what might be called a full menu of all the troubles in my life while still too young to read it."

His nihilistic determinism was inset within him from the beginning. He was a lost a soul, a wounded man. And for much of his life he hid his wounds deeply under various masks of Appolonian masculine control, hiding in the forms of author, bodybuilder and political activist.

And life itself confided this secret to me: "Behold," it said, "I am that which must always overcome itself."

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

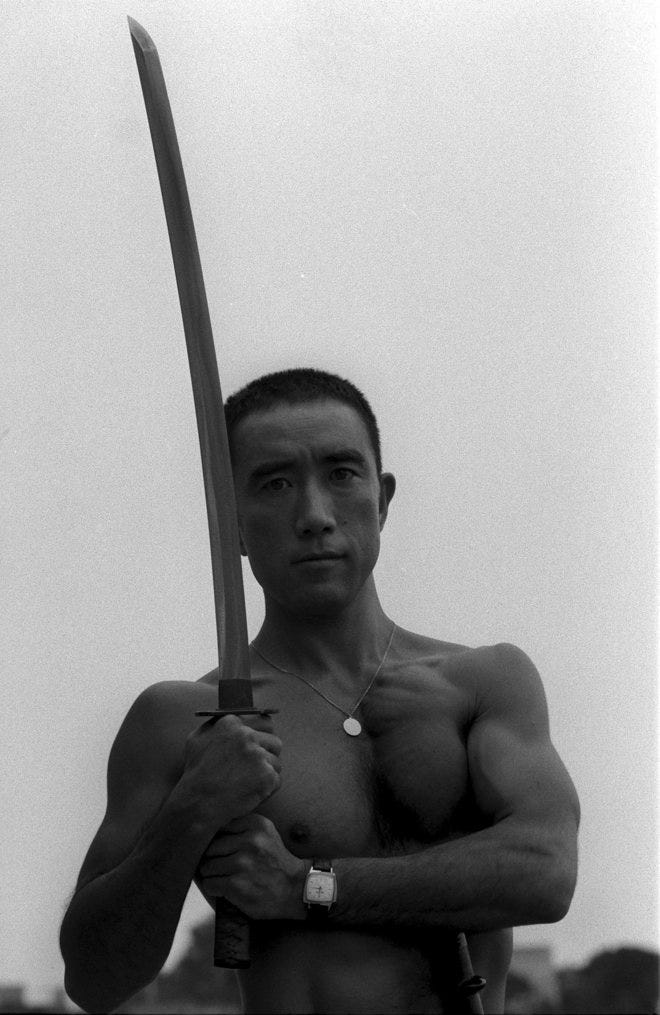

Emerging however from this fertile sea of dark experiences was something golden, wrapped in pure, glittering light. Mishima, instead of balking from his terrifying psyche, spent his life sublimating it. A bold voice cried out within his soul that he could not go through life as nothing – that he had to become himself, that he had to create himself, if anything to avenge himself upon a life that he could not find worthy of his living. His longing for death and night and blood he sublimated into some of the most popular and most beautiful writing written in Japanese. His homosexuality he used to transform his own body into a beautiful, erotic work of art. In an era that glorified scientific nihilism and Western profit obsession above all else, Mishima decided instead to become a decadent romantic, believing in a past and an Emperor that may never have existed as he wished they had. It was no matter what had really existed, however. He only needed to believe.

He turned everything spiteful in him into some advantage, some new power. He did not run from life and flee into some life negating No. He did not fade away into obscurity and hedonism as many a famous writer has. Instead took as much on as he could, becoming writer, poet, playwrite, movie director, actor, swordsman, bodybuilder and finally military man and politician. He turned his feminine emotional sensibility into masculine hardness. He became himself.

"Away from the steel, however, my muscles seemed to lapse into absolute isolation, their bulging shapes no more than cogs created to mesh with the steel. The cool breeze passed, the sweat evaporated - and with them the existence of the muscles vanished into thin air. And yet, it was then that the muscles played their most essential function, grinding up with their sturdy, invisible teeth that ambiguous, relative sense of existence and substituting for it an unqualified sense of transparent, peerless power that required no object at all. Even the muscles themselves no longer existed. I was enveloped in a sense of power as transparent as light." — Mishima, Sun and Steel

Mishima needed desperately to escape the terrifying, limitless realm of potentiality, the horrifyingly abstract nature of “artist” and the trade of words. He needed to become something. His will had to be tested against the mettle of reality. But how does one take action in the nihilistic hellscape of modernity? In order to act, one must first believe. For Mishima, their remained nothing to believe in.

As Kierkegaard describes in his work “The Present Age”, we are trapped in an age of endless reflection, a dispassionate age of aimless thought. All men are leveled by the times. All seek comfort and warmth, staring into the soft heat of the fire and blinking. The Nietzschean Last Man aspires to become abstract, to become nothing. In being nothing one is full of potential that is never actualized. One is free to dream for one must never be, and Narcissus stares into the pool of water forever, simultaneously becoming everything and nothing.

Mishima needed to escape such an existence. He had to become real. He drove and searched desperately for meaning. And what he found, I believe, was meaning in beauty. As he writes in Spring Snow:

“His eye was caught by the iridescent back of a beetle that had been standing on the windowsill but was now advancing steadily into his room. Two reddish purple stripes ran the length of its brilliant oval shell of green and gold. Now it waved its antennae cautiously as it began to inch its way forward on its tiny hacksaw legs, which reminded Kiyoaki of minuscule jeweler's blades. In the midst of time's dissolving whirlpool, how absurd that this tiny dot of richly concentrated brilliance should endure in a secure world of its own. As he watched, he gradually became fascinated. Little by little the beetle kept edging its glittering body closer to him as if its pointless progress were a lesson that when traversing a world of unceasing flux, the only thing of importance was to radiate beauty. Suppose he were to assess his protective armor of sentiment in such terms. Was it aesthetically as naturally striking as that of this beetle? And was it tough enough to be as good a shield as the beetle's?

At that moment, he almost persuaded himself that all its surroundings - leafy trees, blue sky, clouds, tiled roofs - were there purely to serve this beetle which in itself was the very hub, the very nucleus of the universe.”

For Mishima, action again became possible through beauty. His life would be one of aesthetics, beautiful and pure. And he lived up to this ideal in every moment of his existence.

When I first heard of Yukio Mishima a thought flashed through my mind, sudden and all encompassing: "my God, here is a man who has taken Nietzsche seriously." He is and remains to me one of the foremost "attempters" and "free spirits" Nietzsche heralded in Beyond Good and Evil and his Zarathustra. I became obsessed with him and his work. Here, finally, a man who has lived! Here, a human being! Yukio Mishima, first born of the twentieth century, un homme nouveaux. The thought drove me forward: following Mishimas example, we might today still live.

Something nagged me about him, however. It didn’t all fit. His strange, quiet nihilism staunchly refused to disappear from his works. I always assumed he would outgrow it. But it refused to be overcome. As Roy Starrs writes in "Deadly Dialectics":

"What [Mishima’s active nihilism] lacked so conspicuously was Nietzsche’s ecstatic, half-crazy joie de vivre, his ‘Dionysian’ frenzy, his desperate need to ‘justify’ life at all costs..."

In the end Mishima could not defeat his nihilism. He could not overcome his metaphysics of death and night and blood. His will always longed for nothing, for oblivion – to shatter the masks he wore his whole life and reveal the emptiness beneath. This is where Mishima differs from Goethe as described by Nietzsche in Twilight of the Idols:

"Such a spirit who has become free stands amid the cosmos with a joyous and trusting fatalism, in the faith that only the particular is loathesome, and that all is redeemed and affirmed in the whole — he does not negate anymore. Such a faith, however, is the highest of all possible faiths: I have baptized it with the name of Dionysus."

If Goethe is the archetype of transcendent faith turned into righteous action, Mishima, then, is a beautiful but diseased version of this archetype, a tree of twisted oak ensnared in dark green vines. The vines of passive nihilism were bound to overtake him. His seppuku was at once both the culmination of his aesthetic and romantic ideals and a final act of life negation, a grand and theatrical No, a screaming of "fuck you straight to hell" so common to the nihilistic outlook of the Japanese of his era. We cannot, as we can in Goethe, find a model for life in Mishima. In Mishima, one instead finds their model for self overcoming and achieving aesthetic perfection - aesthetic perfection which must necessarily lead to death.

Even still, he holds a fascination for me in the same way that fire does. He was a beautiful, violent dance of colors, spinning evocatively – beneath which hid complete and utter nothingness.