Part 1: A Parable

Let me tell you a story so you can know who I am.

In my review of Kierkegaard’s Either/Or, a hypothetical author writes a letter to a hypothetical young man in which he describes a lock between the young man and others, a kind of social lock; the lock is rusted, it won’t turn, the key won’t quite fit. This social lock bars entry for others into the young man’s world; as much as the young man tries and tries, the door to his heart will not open and allow free passage. And yet, the author says, the young man is sociable, pleasant, people enjoy being around him; no one but he seems to feel the painful presence of this lock. For him all socializing is a kind of torment in which something is always not quite right; somehow, he cannot connect to anyone else, something is wrong, he cannot reach out and touch the heart of another. I think it’s pretty obvious that in this metaphor I am both the young man being written to and the author writing. All my life, from a young age, I felt this social disconnect, the lock that won’t quite turn; for much of my life every social interaction has seemed a complete disaster, ridiculous, awkward, embarrassing, to the point that I feel sometimes a near physical pain. When I was in high school, I was especially sensitive to what I said, how I moved and spoke; I analysed and overanalysed everything I did. Nothing social came natural to me. I was always putting on a poise, saying things I didn’t feel or mean, putting up a social front. I was never able to be natural. I was painfully embarrassed to put people through this song and dance, feeling they knew immediately that I was acting, that I was – lying. I thought no matter how well I faked it they could smell the awkwardness on me. When I say I am a sensitive young man, I mean it. I am sensitive to a fault.

I would watch the “jocks,” the “cool kids,” and what made me most jealous was not their status, or their looks, but their ability to easily fit into any social environment, to know exactly what to do or say. And yet even that isn’t quite right – what I wished I had was their lack of self consciousness, their lack of “putting on a front.” They did what I did with great effort easily, naturally, like it was no more difficult than breathing. They didn’t have to act at all. For this I resented them. “For them it’s easy – for them its natural – but everyone knows that you are a liar, a fake, that you’re putting on a front,” I would think to myself. “They can smell it on you a mile away. They put up with you out of politeness.” This thought – that they knew I was faking, and were only being polite, that everyone must be “putting up” with me – bore into to me like nothing else. I was ashamed of myself.

When I started reading seriously it was because I wanted to understand myself. I wanted to understand why I was the way I was, and how I could change it. I needed a solution, and I turned to books – philosophy and psychology. I wanted to rid myself of my hypersensitivity, I wanted through training and effort to make myself socially at ease, easy to talk to, funny, charismatic. I wanted to make myself a natural, like the others. I wanted to discover the origin and cause of my social deformity (and that was what it was to me – a deformity). I wondered in horror if, deep down, I was “matter wrongly configured,” born incorrigibly wrong. I wondered if, at bottom, I would never feel at ease, if something was broken inside me fundamentally – I wondered if, no matter how many hours I spent trying to socialize, it would never be natural – it would always be an act, it would always be false appearance. My shame before myself grew. The painful lock would never turn easily. The door, it seemed, would always remain shut.

I don’t know if my feeling towards the socially capable was always envy, but it certainly became that. It was unfair that they could do so easily what took me such effort to do. They didn’t even understand – were too stupid to even appreciate – the position they were in. I was smarter than them, more intelligent, more deserving of the abilities that they seemed to be graced with from birth. It was here, in my feelings of envy, that my reading began to bear fruit. The more I read of psychology and philosophy, the more I began to understand the social games that everyone was playing. Through my reading I began to achieve a kind of revenge.

What I came to realize was that the cool kids weren’t being natural either, they were acting too. Everyone was. It wasn’t just me that was faking it – it was all of them! They were only better actors than me, that is, better liars, more easily able to swindle their way through the minefield of high school social life. I saw things for what they were. Fake it till you make it, said the internet blogs I read, and I came to realize that all these people were nothing but fake. The cool guys were just putting on cool personas, acting the way they thought a cool guy should act, in order to impress the girls – so that they could sleep with the girls. The girls were putting on personas too – the rich girl, the preppy girl, the sporty girl, etc. – formulating their lives to characters in television, in order to convince the audience, everyone else, that they were a certain kind of girl. Everything these people did, I realized, was for some other reason. There was always an ulterior motive. Usually this was both sex and status – to actually sleep with someone was one thing, but to be known as the kind of person who gets laid was another – and far more important. It was all so obviously fake to me. Most enraging of all were the popular guys, who were so obvious in their fakeness. And yet, the girls seemed to fall, over and over, for their blatantly fake personas! I couldn’t understand it. Each time I watched Chad with his easy smile talk to some cute girl, my resentment and envy grew. How could she like him? He’s a tool, he’s stupid, and above all he’s so obviously a liar, pretending to be someone he isn’t. And yet it worked for him.

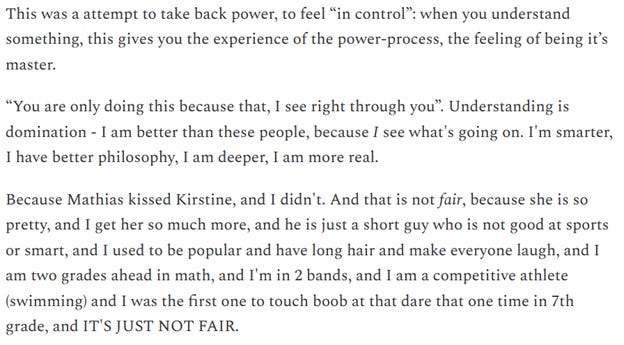

I adopted ironic humor, grew out my hair, dressed differently, acted strange, all as a kind of vulgar outburst, so as to say – I am different from you, but I see right through you – I am better than you because I understand that you are lying. I refuse to play your stupid games. I see the true world beneath your false appearances. Of course, all the knowledge I gained reading books and blogs was not actually usable in any way, it didn’t make me any better socially – it was enough for me to understand what they were doing. Being smarter than everyone else was enough revenge. Sexual humiliation and the birth of philosophy, hooooo boy was it ever.

The thing of it was that all my philosophy was cope. Of course it was. I was 16 and I was afraid of girls and I was being a pussy about the entire thing. I was afraid to put myself out there, afraid of social failure, and just a very self-conscious person who needed more than anything to get out of their own head. Unfortunately, I instead retreated further into my own head. I invented an entire psychology, a whole system of philosophy, to cope, and this philosophy did four important things for me:

Firstly, my new philosophy declared that the social rituals and interactions I saw playing out all around me were fake, justifying my past social failures as not failures but rather an inability and unwillingness to be fake like everyone else (that is, I kicked my social inability upstairs into a moral inhibition: I am simply too naively honest to act as all the liars do.) I turned my inability into a naïve virtue.

Secondly, my philosophy showed that I had “figured out” the “reality” of social interaction, that I had uncovered that beneath all the appearance was a zero-sum game being played for ulterior motives. For sex, status – it was all for something else, and I knew it. This made me smarter than everyone else and justified my present refusal to act – turning my cowardice into an intellectual refusal to partake.

Thirdly, and most importantly, through this philosophy I got my revenge on all those who I envied. I was now not only justified past and present in my failures, but also morally superior to all the stupid cattle who earnestly took part in the social games. Now, knowing everything was fake, and having figured out that all social interactions were mere power game, I had created for myself a lofty position from which to condemn. I could look down especially on all the fools who believed in the personas of the cool kids – what sheep they were! And the cool kids themselves were instantly transformed. They weren’t cooler and more desirable than me anymore – no, they only appeared that way. They were in reality liars and fakes and cheats. I, on the other hand, was no longer an uncool loser who couldn’t talk to girls – because I refused to play the social game, I was now the only honest, pure and true person in a sea of falseness. I became morally superior to everyone else.

Fourthly, having realized my moral superiority, my blind rage for the cool kids was no longer a symptom of envy but justified moral righteousness – unlike myself, who is real and true, they are liars and snakes, and they deserve to be hated, they deserve to be brought down a notch, dragged into the mud with the rest of us. My rage, manifested as vulgarity, was transformed into morally justified revenge.

Take note of the steps I take here. They lead to a pleasant conclusion: “I’m not a loser because I can’t talk to girls – I’m actually more honest, and smarter, and better than you because I refuse to play your games. In reality, you are the loser.”

Eventually, I grew up a little and gave up this line of thinking. Eventually, I came to realize that socializing is not so hard if I just get out of my own head and actually listen to the other person instead of worrying about how I look and sound. I was, in the end, too concerned with myself. Forgive me, it’s hard to understand such a thing when you’re 16. I realized that socializing isn’t about you at all, but entirely about the other person, about listening to them, and in that way bridging the gap between two separated Others. Unlocking the social door is not a matter of them getting past the lock but of myself stepping out, of myself forcing open the door. And I came to realize that all the fake social interactions I had thought were just games in the social power struggle were actually tools for bridging the gap between myself and others. The “scripts” which I rejected as utterly false existed purposefully so that two strangers, otherwise unknown to one another, could converse, could meet on the street without hostility and suspicion but instead as friends. The way you bridge the gap between yourself and another is by manners, by being polite – “how was your weekend?” “how are you today?” – sentences I once considered canned, lies, appearance – these rituals were designed exactly to solve the problem I faced. They were precisely what I needed. By following these rituals, and slowly, ever so slowly opening up – being vulnerable, straying from the script and revealing parts of yourself, bit by bit – you could make friends.

It is exactly when you make yourself vulnerable, when you show your soft underside and open yourself up to getting hurt, that the process of friendship can begin. This vulnerability says “I am willing to be hurt, because I wish to meet you. I am ready to give something of myself up, for no logical reason but that I believe that we could be friends.” It is a leap of faith. It was this that I could not do as a teenager. I was too afraid. What I was missing was the public space and the very canned lines I so hated. But I am getting ahead of myself.

Why do I tell you this story? Who cares? The philosophy I invented when I was 16 was one of resentment, envy and rage, invented to quell my shame, justify my failures, and create the opportunity for revenge against the dominant culture. I want to give you here in microcosm an example of how such a philosophy comes to be. In particular, I want to point out the purpose of such a philosophy, to understand what such a philosophy as mine was invented for.

I would like to make clear to you, by my description, that the psychological problem of shame occurred first, followed by envy, then rage, one after another in succession, with the final logical result of this process being the invention of a philosophy that despises the world while asserting moral superiority to it, a philosophy that claims to see the “truth” of the world beneath the mere “appearance” that seems to fool all others. I want to show you that the result of my failure to overcome my own shame was a reorientation of all my psychology, my whole interpretation of the world, around my own weakness, resentment and impotence. Shame occurred first; all the rest, by logical necessity, followed.

I think this has a lot to do with Freud.

Part 2: Shame

“Gradually it has become clear to me what every great philosophy so far has been: namely, the personal confession of its author and a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir; also that the moral (or immoral) intentions in every philosophy constituted the real germ of life from which the whole plant has grown.” – Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

When we are young, we are taught to take intellectual statements at their face. When someone says to you, “I believe in such and such a thing,” we are taught in the free spirit of inquiry to think “well, that is an interesting position – I will consider it, and in my consideration assume you are being honest and truthful when you tell me that this is what you believe.” We don’t look for motives behind the thought of others – because it is impolite. Innocent until proven guilty. My dad puts it this way: we are all boy scouts. We assume people are good and have good intentions.

This is not to say that people are naïve in their dealings with the world. No, in regular life people are very shrewd. They are naïve instead in their dealings with ideas. When someone presents us with an idea, we argue with the idea itself, and not with the speaker. It is considered rude to argue with the man behind the idea, or to even consider why it is that he in particular would have such an idea in the first place. Arguments must instead be defeated in the open marketplace of ideas. They must succeed or fail on their merits alone.

Westerners are in many ways incapable of arguing against the man. They can only argue with his ideas. While the true motivating force of many a debate often stems from raw hatred between the debaters – think of every Ben Shapiro style YouTube debate video you have ever seen – the arguments the interlocutors make will always attack the ideas of their opponent, not the opponent themselves, because to attack the man behind the idea is seen as rude, as a “low blow”.

This is a matter of manners. It is impolite to assume ulterior motives, to assume, from the outset, that a person is trying to trick you. Instead, each man receives the benefit of the doubt, the ideas of each man will first be considered fairly before they are dismissed. This attitude fails in that it assumes interlocutors who are equal, who are raised equally, and have the same manners – people who come from the same culture of high trust – it assumes peers who do, genuinely, seek knowledge for the sake of the Good and the True. This fails when the opponent is not seeking knowledge in their pursuit, but seeking – something else.

Why was it Freud of all people who discovered the Oedipus complex? Did he discover it, or did he invent it? Why did it take a Viennese Jew – that is, an outsider, a pariah in Protestant Europe – to diagnose the sexual neuroses of the Western world? There is a long-standing idea that it is only the outsider who can see through the lies of the ingroup, that only the one outside the system can understand the “true motives” of those working within it. Only the outsider can see the water in which all the fish swim. But is not pointing out the water merely – a vulgarity, from resentment? Don’t the fish know how they live? “If I’m not allowed in your group, I’ll show you what you really are! I’ll show the entire world your dirty laundry!” When I was a teenager, I did not sit at the cool kid’s table. Instead, I read philosophy and psychology – in order to get a leg up on the cool kids, so I could say “Because I am not invited, I am able to see through your lies.”

When Freud was twelve years old his father told him a story, recounted in Chapter 4 of John Murray Cuddihy’s Ordeal of Civility. Freud’s father had been walking through the streets of Freiburg many years before, well dressed, with a new cap on his head. This was before the Jewish Emancipation; he, being a Jew, was a second-class citizen. As he walked, he came across a Christian, who in a single blow knocked the new cap off his head. “Jew! Get off the pavement!” shouted the Christian. When the young Freud asked his father what he had done next, his father told him not of any heroic revenge but in a quiet voice said that he had obediently stepped aside and collected his hat off the ground.

Freud described hearing this story as “the event in my youth whose power was still being shown in all these emotions and dreams.” Freud tell us how he immediately contrasted the story against a story that “fitted his feelings better”: the story of Hannibal’s father, who made Hannibal as a child swear to someday take revenge against the Romans who oppressed the Carthaginians. “Ever since [hearing my father’s story],” Freud tells us, “Hannibal has had a place in my phantasies.”

What was the power of this story for Freud? Why did it hold such a grip over him? The power of this event for Freud, Cuddihy contends, is to be found in shame. When Freud’s father told him how he had obediently stepped aside for the Christian, Freud felt shame. A deep-seated shame of his own father was born, a shame so deep that the adult Freud continued to feel it decades later. It was revealed to Freud that day that the “powerful man who held the hand of the little boy” was, in fact, a slave, powerless in the face of the Christian oppressor. What Freud began to feel that day, and would continue to feel, was first shame at his father, and secondly, a corresponding shame of himself, a deep, unrelenting shame. The childhood image of the father, as an all powerful, all capable figure, was shattered; instead, it was revealed that not only was his father powerless, but he himself, the son, was just as powerless. When the Christian shouted, “Get off the road, Jew!” the shout reverberated in young Freuds ears, too – he was a Jew, he was lesser.

Freud’s philosophy begins here, critically, in the shame experience. Shame at the impotence, the submission of his own father; shame at being a member of the outgroup, of being lesser-than. That is its nexus; a shame so immense and so deep that it had to be solved, that it could not be lived with. As a teenager, I could not live until I knew what was wrong with me socially, I could not bear the shame of my social failures; Freud could not live until he had somehow dealt with the shame of his father’s impotence, which was, then, his own impotence. This is the kind of obsession that bores into the mind like madness, it is the kind of problem that keeps one up, wide awake, into the early hours; life is unable to continue until it is resolved, until the problem is solved, or transformed, or sublimated, or until you yourself are destroyed. There is no way out. The only possible avenue is through.

Shame becomes rage and resentment; the enemy must be deprived. What they have must be taken from them. Why was it that Hannibal immediately became a part of Freud’s fantasies? Because like Hannibal, Freud must also have revenge on the enemies of his people. Hearing that story, his fantasies become dominated by Hannibal; Freud swears revenge that day, he knows then what he must do. But where will Freud find a weapon to use in his revenge against his oppressors? He will find it in his novel interpretation of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannos.

“The story his father had told him at ten or twelve, I shall argue, bears an uncanny resemblance to the event that precipitated the Oedipus story: the chance meeting on the street, the incivility of the threat to “thrust [one] rudely from the path.” This time [in Oedipus] the son doesn’t “take it lying down” but, when “jostled,” strikes back in anger at the driver. Then, just as with Freud’s father years back, Oedipus is struck “full on the head”, but this time, instead of the “unheroic conduct” of his father meekly fetching his cap out of the muddy gutter, Oedipus in his fury strikes back again and kills... his father.” – The Ordeal of Civility, Chapter 4

Here we see the double motion of Freuds shame. Shame is a mover, it moves you to some kind of reaction, and for Freud two reactions were necessary. Firstly, revenge against the oppressor, against the socially superior – remember that in Oedipus, Laius is the king, demanding the unknown peasant wanderer Oedipus step aside. When insulted this way by the socially superior (here the Christian gentlemen on the street), Oedipus does what Freud wishes his father had done. He does not bow meekly but instead in a violent rage kills the social superior on the street. Freud identifies with Oedipus as he identifies with Hannibal, both are objects of fantasy for Freud, fantasies of violent revenge against the oppressor. However, destroying the oppressor is not enough to quell the rage; the second motion of Freuds shame is revenge against the father. It is not just anyone who Oedipus kills, but his own father, Laius. Freud is ashamed of his own father, and he will deal with this shame by – killing him.

As an adult Freud saw Oedipus Tyrranos performed and could not shake the play from his mind. He needed to figure out why the play had such a grip over him. This grip troubles him, he cannot understand it, he can’t shake it, the problem bores into the mind like madness. So he develops a theory of psychology. “A legend has come down to us from classical antiquity: a legend whose profound and universal power to move can only be understood if the hypothesis I have put forward in regard to the psychology of children has an equally universal validity.” And what follows is his famous theory: everyone’s secret desire is to kill their father, and sleep with their mother.

If you know anything about dream interpretation, you’ll see that Freud fails from the outset to follow his own principles. He takes the manifest content of the play, Oedipus killing his father and marrying his mother, as the secret wish of all mankind. But the manifest content of a dream is not a direct expression of the secret wish of the dreamer (that is, the dreamer is not dreaming of the thing he really desires). The dream exists in order to hide the dreamers wish from him, and the manifest content of the dream is what does the hiding. The manifest content defends the dreamer from the truth of his wish. The wish is secret and hidden, and must be defended against, because it is too horrible to be made manifest – it cannot be known directly. Freud’s philosophy manifests as an objective psychological science describing the minds of men, but the secret wish of his psychology, the one so horrible it must be hidden and distorted, is for revenge against the Christians, for revenge against the impotence of his own, shameful father. The play is gripping for Freud because the manifest content of the play hides his own secret wish, while the latent content fulfills his secret, horrible desire: Freud’s shame, like Oedipus’, wants revenge.

“The “parricide” Freud committed was committed by Freud’s shame of [his father]. The opposite of shame is courage… Oedipus Rex enables Freud vicariously to convert passive shame into active courage, avenging himself and his father against both his father and the general culture. Oedipus Rex, in fantasy, “solves” many of Freud’s “problems.” But everything begins in the shame experience... Freud mutates the shame into guilt, since it is more tolerable because more alterable to want to kill your father than to be ashamed of him. (And, besides, Freud in fact does experience guilt as part of the complex emotional “complex” he suffers, but it is the “guilt of shame,” the guilt of having “deauthorized” the parent, not the guilt of having entertained the forbidden wish to kill him in order to possess the mother.) It is more permissible and tolerable to own up, to blame yourself for being a parricide (in fantasy), than to be ashamed of your father (in reality) for his, and consequently your, misfortune in having been born a Jew. So Freud converts the shame into guilt. He transforms the sociohistorical “givenness” of Judaism into the psychomoral “takenness” of Jewishness. From a misfortune it becomes a problem. From historical tragedy it becomes a solvable scientific problem.”

“The superego and its ideal is formed, as Freud taught, to compensate for the loss of the parental “object-cathexis.” Freud, on the day he heard from his father’s lips the story—to him, ignominious—of his father’s encounter with an “enemy of our people,” at that moment in his shame and rage he “slew” his father, adopting the more heroic ego-ideal of Hamilcar Barca.” – The Ordeal of Civility

Cuddihy is a little too kind to Freud, in my opinion. He says Freud was “helpless to take the mythos of Oedipus as knowledge, thus transforming Sophocles’ tragedy into a cognitive theory of psychosexual development and sending it out into the world as psychoanalytical ‘science.’” Too kind, because firstly, if you read Oedipus, it becomes rapidly clear that the actual meaning of the play has nothing to do with killing your father and having sex with your mother. “Killing your father and having sex with your mother” is a literal summary of the actions of the characters. If this is all that Freud took from the play, he either had an eighth-grade interpretative ability (he didn’t), or he was hiding from the real meaning, distorting it to himself. Secondly, and more importantly, Cuddihy seems to disregard here that Freud’s philosophy had a purpose. His philosophy was not arrived at through logic and thought in the service of Truth, it was created to be used, it is knowledge used as a weapon. Its goal is revenge; its goal is transforming Freud’s own shame into active courage without any action on Freud’s part. His psychoanalysis is a weapon forged to strike against the dominant Protestant culture, to take them down, to drag them into the muck. Freud’s philosophy is vulgar; when he spoke of it in public the crowds were shocked at his vulgarity, his willingness to talk openly of penises, vaginas, sex, his excitement to reveal how they all, secretly, longed to sleep with their mothers and murder their fathers; how beneath all the decorum of their Christian society lay the base animal desires, for sex, for money, for power. Freud shoved their dirty laundry right under the Christians noses, and he took great delight in doing so. “Though you pretend to be refined, you are, deep down, dirty.”

What I am saying is not that Freud was unconsciously driven by this need for revenge, and that this need manifests in his creation of psychoanalysis in order to attack Protestant Christianity. You’ll note how that interpretation removes all responsibility from Freud. There is nothing unconscious about what he was doing. What I am saying is that Freud is actively driven by shame, resentment, revenge, rage, here lie the immoral roots that are the real germ of his philosophy. The revenge motivation is not unconscious, resulting, inevitably, in the philosophy; Freud’s motivations are perfectly conscious, and all the trappings of science he layers on top of his rage are merely lies. He intellectualizes his rage, the same way I did, and this accomplishes for him a great deal.

When people confront Freud, they are only able to confront his ideas. But his ideas exist in order to obfuscate their purpose. All philosophy has a goal; it is no mistake that it was Freud who “discovered” that the Christians were, secretly, vile and evil animals, driven by base desire. It is no mistake at all.

Part 3: The True World

“Excremental things are all too intimately and inseparably bound up with sexual things; the position of the genital organs—inter urinas et faeces—remains the decisive and unchangeable factor. . . . The genitals themselves have not undergone the development of the rest of the human form in the direction of beauty; they have retained their animal cast. And so, even today love, too, is, in essence as animal as it ever was.” – Freud

“You should look closely at the direction of the force vector, it starts not from ethics or equality but envy.” - Sadly, Porn

A philosophy never stands on its own. No system of thought is arrived at freely, the result of pure logic and rationality. When I decided to “understand myself” and “learn about psychology”, I was not learning in order to learn, from desire for knowledge, I was learning in order to use my knowledge as a weapon. This was a weapon of resentment. What I wanted above all was to unmask the lies of others, to show their “false world” for what it was – a lie. To show all their social prowess as mere game played for ulterior motives. Because if their false world was a lie, it proved that I was not “lesser,” it proved that my own unbearable shame at my inability to socialize normally was not a mark against me – no, I was enlightened! I saw through the games they played! I was not “matter wrongly configured,” but instead, I saw the true world that the others refused to see. And I would show it to them, I would rub their faces in their own dirty laundry.

None of this was unconscious. It was all done on purpose. I was only lying to myself about the true origin of my philosophy. More importantly, I was lying to everyone else.

Freud’s philosophy posits that the sublimation of the animal drives found in Christian society – for instance, the sublimation of the sex drive into the rituals of courtship and marriage – were all mere appearance. He claimed that the animal drives themselves had not been turned into something higher but had merely been hidden. Freud’s philosophy posits that in the apparent world, the Christians had turned vulgar sex into the beautiful relations of marriage, but that this was all only appearance, lies; in reality, the Christians were still consumed by vile animal drives, they still wanted to murder their fathers and sleep with their mothers, they had only made these vile things appear beautiful. This kind of thinking is arrived at in a very particular way, under very particular psychological conditions. I would like to explain its origin. I would like to explain to you the psychology of the slave.

A man becomes ashamed. He has to deal with the shame, he has to solve it. The hard path is to confront the shame; the far easier path, the one Freud took, the one I took, is to instead escape this shame, to flip the world on its head and “discover” why it is everyone else who is wrong; to stab out everyone’s eyes so that they cannot see you in your shame. Confronting the shame requires action, but “figuring out” why you are ashamed requires only knowledge. Knowledge as a substitute for action. This point, the confrontation with shame, is the precipice on which the healthy nature becomes through action, and the unhealthy nature recedes into what he already is.

What does the slave want? He wants to solve the problem of his shame. Changing, himself or the world, is too difficult, for it requires action, and action first requires fantasy. The man who can act can must first be able to fantasize, this is the critical ability that media (that is, porn) today obliterates; the man who can act fantasizes what he wants, by his own values, then he reaches out to take it. The slave cannot fantasize, and I mean that literally: he is incapable of fantasy, he is incapable of creating something new. He does fantasize, sure, but his fantasies are all pornographic, and by pornographic I mean that even in his fantasies he never acts but is only compelled to act. He can fantasize revenge, sure, against those with power, but only because those with power have compelled him, in fantasy, to take action – he could not imagine acting of his own volition. Oedipus could only strike back when he was first struck. Hannibal is a fantasy for Freud because Hannibal is taking revenge.

The greatest thing the slave can imagine is himself as the master of the existing system. What he cannot imagine is a new system. If he were made ruler today (and note the tense: made ruler, by some other omnipotent entity) he would change nothing. His fantasies, like porn, always end in a return to the status quo. He does not imagine a new kingdom: he wants the same kingdom, the same throne, the same queen as the master. He is within the system of values of the master. When the defines power he means “being the man in charge”. Alexander did not imagine power this way, or else he would have been satisfied as King of Macedonia, he would have been sated with his father’s throne. No, he had a different vision, a different set of values; he saw a world ruled by a philosopher king, an Achilles mixed with an Aristotle, he saw an empire that stretched from sea to sea, an empire built on the virtues of Greece, but different from Greece, multicultural, the whole earth united under the Greek language and thereby the Greek psychology; he saw something new. He was not satisfied with Phillips throne; how could he be? So he kept a copy of the Iliad next to his bed, and a dagger under his pillow; the means to action within reach and his fantasy just barely outside of it. He created his own values. You can agree or disagree with Alexander’s vision, but that is all you can do, because the slave can only react to the values of the master. Reaction is the only kind of action the slave has.

The slave cannot change the world, so he learns about it. He invents philosophy and trades action for knowledge, he trades power for knowledge. He “discovers” that the rules that govern reality, the ones that have made him so ashamed of himself, are only appearance; and that underneath this appearance are the animalistic true motives of the participants. The slave invents the true world and the apparent world, and in the same sentence declares that he is the only one who can see through the false reality. I “discovered” that the cool kids were all “fake”, that they were only putting on fronts for one another; all the music they liked and clothing they wore were only being used as social indicators to show others that they were “cool”; that underneath it all was their narcissistic psychology, their social posturing, and most of all their animal psychological desires. And in this way, I was no longer a loser, but instead “above” such games of appearance. In this way, I would never have to act, or change. I could remain aloof and cynical, above it all. I, like Freud, successfully flipped the order of values on their head. Now the bottom was the top, and I was king.

Freud enters as a young man into the Jewish Emancipation and like all Jewish intellectuals of the time is immediately aware that the Jewish shtetl culture is, in contrast with the culture of Western Protestants, uncivilized. By uncivilized I mean “without civility”, literally “without manners”. The shtetl life is a life “with people.” The shtetl is, to use our contemporary term, the longhouse. As Randy explains in his excellent NPC question series, the distinction between public and private space does not exist in the shtetl. There is no concept of the “owned space”, there is no distinction between the public and private self. The culture is tribal. There are no locked doors, there is no decorum, there is no – civility.

What Freud understands, entering into Western civility for the first time, is that the West has sublimated the coarse sex drive into the higher concept of Love, through civility, through courtship, and he thinks it’s a lie. He sees it as mere appearance. Nietzsche talks of the paradoxical nature of sex becoming love under medieval Christendom. This is able to occur thanks to inhibition. A slave can only react, an animal can only react to its drive. But men act, men are able choose and thus act freely. They are not compelled by their drives to respond, but are able to withdraw, to think, to decide, to choose, then to act. The slave uses knowledge to avoid action, but the free man uses knowledge in order to withdraw, so that he can act with the apprehension and the intelligence of the Gods.

Christianity sublimates lust into the higher institution of Christian love. The sex drive makes it’s demands, but the Christian man, through civility, must step back, for he cannot merely have what he wants; his drive is inhibited, and instead of buying the hand of the girl he desires, he courts her, following the rituals of courtly love. The sex drive is ennobled, it is inhibited, it is made to wait, it is allowed its expression only in love, in verse, in beautiful words and promises. Immediate pleasure is put off for far greater rewards.

By contrast, in the shtetl, marriage is arranged by a matchmaker, and the pros and cons of a marriage are bartered for in precisely the same way any other commodity. For Freud, this is the “true world”; Christian love, with its rituals and its inhibition, is mere appearance, is one of the many goyim nacht (goy games) that the Christians play to convince themselves they are more refined. They are lying, thinks Freud – all their courtship and love poetry is mere pretense, mere appearance, covering their true, brute animal desires. Freud takes great pleasure in telling his Christian audience this fact. He deprives the Christians of their refinement. Love is still caught between urinas et faeces, he tells them. It is as animal as it ever was. Tearing down the appearance of nobility – this is how he achieves his revenge.

"Feudal Catholicism and, later, bourgeois Protestantism took hold of lust and institutionalized it, in the course of a long sociocultural revolution, into love. Freud, entering the West in the late nineteenth century, using a pre-modern, coarse, pariah model of the sex drive, proceeds to unmask the whole thing as at best a pious fraud."

“Freud disbelieved in romantic love. There is an old Yiddish proverb—“Zey hobn zikh beybe lib—er zikh un zi aikh: They are madly in love—he with himself, she with herself”—that expresses his scepticism. For Freud, courtoisie is a decoration of sexual intercourse in the same way that courtesy decorates social intercourse. His deepest urge was to strip both of their courtliness. He experienced both as a hypocritical disguise that must be stripped away, like any “appearance,” exposing the “reality” underneath.” – The Ordeal of Civility

Unmask, strip away the hypocritical disguise – Freuds goal, as in all slave philosophies of the true world, is to reveal the hypocrisy and lies of the master and his apparent world. Freud is pulling back the curtain on the appearance of refinement to show us the “true”, brute animal world hidden underneath. Refinement under psychoanalysis becomes repression. Repressing an impulse – an animal desire – becomes a sin, because it is “untrue” to the “real” self. Refinement no longer elevates the desires into something higher but is instead under psychoanalysis only a comforting lie. Thus the Christians are stripped by psychoanalysis of their claims of refinement – they are dragged down into the shtetl, into the dirt and mud of “war against all,” with everyone else.

This is how Freud escapes his shame. Freud is avenged, like Hannibal, against the enemies of his people, by dragging them down into the mud with him. He no longer has to act, he no longer has to change to escape his shame, because he has proved that their world and its social rules are all a lie. He is above them now. The greatest victory for the slave, the greatest thing he can imagine, is not a new system but to deprive the master, this is the most satisfying and sweet revenge. Freud, having built the moral edifice from which he will condemn, can now have his sweet revenge: he deprives the master of all his refinement. Deprivation is the goal of his philosophy, of all psychoanalysis. Look closely at the direction of the force vector propelling Freud’s philosophy. It is rage.

Part 4: The Shtetl, the Longhouse

Why does any of this Freud stuff matter? Who cares? “No one believes in Freud anymore.” It’s true, we’ve defeated Freud with studies and science and now all his bunk psychoanalysis is laughable to our empiric minds. Yet the form of his argument is the most popular one on earth, look around and despair: his argument is an argument for the true world, it is resentment. Everyone believes the same thing: if only someone saw who they really are, not who they appear to be under the false rules of the world, then the world would know their true greatness! We invent a better world from which to condemn life; we flip the values of the world on their head so we can claim first moral superiority, then intellectual superiority. Finally, we reach our real goal – with our newfound philosophy, we justify our own envy and rage as morally correct.

It was Plato who first realized that this idea was far stronger as an intellectual position than a religious one originating in the authority of the priests. He invented his immortal forms, perfection that exists in some abstract elsewhere, he invented his perfect republic and claimed that we mortals and our society were only failed imitations of this perfection. The instinct in Plato is an instinct of sickness – writing at the end of Athens height, writing in an Athens obliterated by Sparta, he invents a better world from which to condemn his own. Socrates knew it too – his dying words, “I owe Asclepius a rooster,” were a confession – he was sick of life, and in death, was cured. Then comes Christendom, we the meek shall inherit the earth – we the meek shall be rewarded in heaven, though in the here and now, we are weak and impotent. This is where Nietzsche’s entire critique of Christendom originates, this is the starting point of sickness, ressentiment. This, gentlemen, is the essence of all philosophy.

“The true world, attainable for the wise, the devout, the virtuous—they live in it, they are it.

(Oldest form of the idea, relatively clever, simple, convincing. Paraphrase of the assertion, “I, Plato, am the truth.”)” - Twilight of the Idols

“I, Plato, am the truth.” – and what did Freud say, when he declared his theory? “A legend has come down to us from classical antiquity: a legend whose profound and universal power to move can only be understood if the hypothesis I have put forward in regard to the psychology of children has an equally universal validity.” I, Freud, am the truth.

Freud’s idea of a true and apparent world was not his own invention, but only the most recent innovation in a long line of similar slave philosophies. Many before him had seen the utility in these philosophies, in the way they invert the values of the world. Such ideas do not appear in a vacuum; they are instead the extension of the environment from which the slave originates, the longhouse. The slave philosophy is the natural extension of the conditions of his world.

“In the Jewish subculture from which Freud and the majority of his patients had emerged, there was no privacy as such. “It is proverbial,’ Zborowski and Herzog write, that “there are no secrets” in the shtetl.... It is a joking point rather than a sore point, because basically the shtetl wants no secrets.... The great urge is to share and to communicate. There is no need to veil inquisitiveness behind a discreet pretense of “minding one’s own business.” ... Isolation is intolerable. ‘Life is with people.’” – The Ordeal of Civility

The fundamental characteristic of civilization and civility is differentiation which becomes refinement. We separate the public from the private, we separate our work self from our home self, we separate the economy from the society, the church from the state. Modernization differentiates the parts of man, and in doing so frees him. No longer is he bound to make political, economic, social or cultural choices based on who he is within the tribe (for the tribal man, the premodern man, all these things are bound together) – each may be considered distinctly.

“The social change fostered by modern differentiations frees man from the old ascriptive cushions, and thus, White observes, it cannot—unlike previous changes—‘“be absorbed for the individual by the family, the church, a class, or an economic or political interest. It is one that the individual must confront by making choices without dependence on ascriptive guidance. He is, indeed,” White concludes, “forced to be free.”” The Ordeal of Civility

In this differentiation modern man is no longer compelled by class or circumstance to react to the world – he is able to step back, to choose, to decide, and to act in absolute freedom. Responsibility is thus his alone. Each these once intertwined, muddle elements of a man are separated and thus are able to be considered in isolation. The fundamental differentiation, the one that informs and makes sense of all these others, is the differentiation of one’s relations in public and in private. In the tribal world, there is no difference between public and private behavior. One behaves at home as one does in the street, because in the tribal village, there is no private home, as there is no privacy at all; everything is collective.

In the tribal world, there is only the private space of the self, and the private spaces of others. In negotiated public space, we agree to act a certain way – there is a “public self” that is governed by the rules of civility. We take common space and define the rules for behavior in this space. These rules and rituals are what allow peaceful interaction; they are what allow two men, unknown to one another, to meet on the road and smile at one another, or nod, or shake hands. Both understand the rules that govern the space they are in, both have agreed to them, and thanks to this, there is no fear. This is what we mean when we speak of the private-public distinction: in private space, you may act how you want, but in public space, you will act by the rules we have all agreed to, so that we can all get along.

In the shtetl, there are no such agreements. I repeat that there is only the private space of the self, and the private space of the Other. There is no public space with agreed upon rules of conduct. The result of this is that you are continuously negotiating the bounds of your private space and the spaces of others. You are always deciding, moment to moment, where your private sphere can expand and where the others must contract. Differences of power between people are what determine what is allowed, as opposed to formalized and agreed upon rules; these differences of power are constantly shifting, such that the borders of each space are always changing and fuzzy. In this world, you cannot ever put down your weapons, you cannot ever be “at ease”, for you never know where the boundary lies and must always be reasserting and defending your own boundary. You are constantly “patrolling the border.”

Imagine a man and his wife who do not love one another. Imagine how their morning goes before work. They come out to have breakfast, they don’t speak, or if they do they say the lines that they have unconsciously agreed on, the ones that won’t lead to a fight. The unuttered tenseness of this situation is palpable. Each will make their breakfast at a particular place, him at the end of the counter, her at the table, and these positions have been hard won by continuous prodding and testing of boundaries, of figuring out through constant little fights and little jabs at one another where they can each exists without active hostility. If any one thing goes awry – perhaps the husband drank all the coffee that morning that was meant for the both of them, or the wife forgot to put bread in the toaster for the husband – a roaring fight erupts. To the outsider the fight is incomprehensible – they are screaming at one another over coffee or toast. But to the husband and wife, the rules of sharing their space, and their entire life, have been carefully demarcated. The bounds of their private spaces have been set. Through tiny aggressions – she rolls her eyes at him when he drinks all the coffee, he snaps at her when she doesn’t put toast in for him – they have determined who has power, and where, and what each of them is to do to exist together. When these unstable boundaries are broken, chaos ensues. The uneasy agreement, made over years and months, is broken and now the balance of power is unknown and must be asserted again, sometimes through screaming, sometimes through angry looks and snide comments, sometimes through months of barely noticeable actions, the long cold war campaign of coldness. In this environment, all resources are continuously fought over, power must be negotiated and renegotiated over and over. Someone will win and the balance of power will be restored – but only through assertion and aggression.

Extend this metaphor into the whole world, and you arrive at the shtetl. Everything is a cold war – your life with your wife, your life with your family, your existence with your coworkers, your children, your boss. In this world the only way you can gain is if another loses. The only time your private, owned space (physical, emotional, intellectual) can be expanded is when the space of another is shrunk. So forever you are baring arms, always pushing against boundaries, testing limits, seeing where someone else has become weak and you can expand. The entire world is zero sum: there is a fixed amount of space in the world, and to gain some, someone else must lose. The exact same plays out in offices. In the office, everyone is cutthroat, trying to gain respect, prestige and favoritism from their betters, and trying to push down their peers so that they can grab at whatever scraps of space and power are available. Here originates the disgusting behaviors we associate with “workplace culture” – sucking up to bosses, grabbing at little, meaningless responsibilities and titles so as to seem more important, the HR mammies who delight in forcing others to play by arbitrary, humiliating rules. Every interaction is politicized, one walks on eggshells constantly, one must always be planning and scheming.

In this world there is appearance and reality, and yet everyone knows the stakes. When someone is nice to another, it is only because they believe they have something to gain, and the receiver and everyone else knows this. When your peer gets coffee for the boss, you think, “well of course he would, that slimy bastard, he’s sucking up because he wants to be the lead for the next project.” The boss knows this too, he is not a fool, he is well aware of the game, and he thinks “I like this guy, and he seems loyal, and knows I can help him – I can use him.” Everyone gets something. To give in any way is a power play. It can never come from genuine charity – it is always for something else.

“I had to laugh at these goyim and their politeness. They aren’t born smart, like Jews. They act like gentlemen to each other. They’re polite all the time so they can be sure one won't screw the other. Well, thank God I didn’t need any substitutes for smartness. I didn’t have to be polite, except for pleasure.” – Jerome Weidman, I Can Get It for You Wholesale

This is what we mean by the tribal world, the Hobbesian war against all. Freuds philosophy is the natural extension of the shtetl psychology of the true world and the apparent world. In the apparent world, you are being polite – but in the true world, you are just being polite for some other reason, and we all know it. This psychology mandates that ulterior motives be the only driver of human interaction. Everyone wants something, and everyone is vying to get what they want – and according to Freud, only the Jew is open about what he wants. The Jew will tell you to your face what he is after – the Protestant is a liar; he hides his desires behind his lies of sublimation and refinement. His politeness is a façade.

Note well that the result of this world is that default and only logical mode of being is constant suspicion. Trust cannot exist in the shtetl, or if it does exist, it is hard won and questionable at best. People I have met who think like this – none of this is theoretical, I describe what I have witnessed – for them trust is not ever truly possible, but loyalty is the highest virtue. But this loyalty only exists as far as it is useful to both parties. The moment there is something to be gained by betraying the other, all loyalty is cast aside.

Because trust cannot exist, neither can privacy. To be private about something in the tribal world can only mean that you are hiding something, that you are keeping something from the tribe. Everyone is involved in the lives of everyone else because we cannot be sure that we are not being cheated. There can be no private spaces, no private lives, because who knows what you might be up to? Warfare and suspicion must be constant. Locked doors do not exist – why would you wish to lock your doors? Are you hiding something in there? Are you cheating us?

When Freud, thrust out of the shtetl, encountered Protestant civility, he experienced the differentiation between the private and public persona as subterfuge. As hiding something. When he sees civility and politeness, he experiences it as a lie that tries to hide the vile, ugly desires of the Id. But what is the purpose of this lie? It is a trick, a goyim trick that lets the Protestants claim moral superiority in having sublimated their ugly animal desires into something higher. That is, this claim to sublimation is how the Protestants get ahead; in the war against all, the Protestants use their civil rites and rituals as a weapon.

“Freud, looking at sexual activity in the West (as Marx had looked at economic activity) finds all its social institutionalization to be so much sublimation, so much “superstructural” disguise of coarse “nature” underneath. He asks of his followers that they not be “taken in by” this superstructure, that they not be suckered by appearances. “The basis of all this,” Max Weber notes, “is to be found in the naturalism of the Jewish ethical treatment of sexuality.” To the economic naturalism of Marx, emergent Western capitalism was mere greed all dressed up in Sunday clothes; to the sexual naturalism of Freud, “love in the Western world” (de Rougemont) is “id” tricked out as “Eros,” is like a “Yid” trying to “pass” as a goy. This is the fundamental metaphor. Freud finds the sexual instinct in the West “essentially” untransformed, un- assimilated. It is stuck between pariah and parvenu much as the Jew, socially, is between pariah and parvenu. Freud is, so to speak, ego—between id on one side and superego (Gentile sociocultural demands) on the other. He warns against assimilation, against “conversion.” The id-“Yid” is essentially untransformable (in Jew as in Gentile). One cannot—one must not—replace the id by the superego (the Jew by the Gentile); one can—one should—replace the id by the ego: “Where Id was, there shall Ego be.” – The Ordeal of Civility

Freud, coming out of the middle ages of the shtetl, is unable to understand the purpose of civility in any context but that of the continuous warfare of the tribal world. He fails to understand what civility is for. To him it must be a Protestant intellectual-cultural weapon in precisely the same way as his psychoanalysis will be a Jewish intellectual weapon. Psychoanalysis is thus reactive, defensive, it is as all slave philosophies a guerilla warfare tool of the oppressed that inverts the values of the dominant culture. The slave can only react to the system of values of the master.

But what is, then, the purpose of civility? The goal of civility is to eliminate the constant warfare of the tribal world. Civility alleviates the conditions of suspicion and mistrust by creating a demilitarized zone, public space. It establishes a system of rules for behaving in this space that allows one to put down one’s arms. This requires the sublimation of one’s own desires, it requires delayed gratification – inhibition – which is experienced by the childlike Id as "acting falsely," but it is only through this sublimation - for sublimation, it is always through - we are freed of the war against all.

The rules of civility are arbitrary and cruel to the tribal mind, they are “mere appearance,” they are a kind of lie because they literally cannot be understood under shtetl psychology. What the tribal man cannot understand on a psychological level – what Freud could not understand – is that the primary action of civility, the adoption of a public self, is not to appear a certain way for some kind of gain, but for the sake of everyone else.

"If you want connection with other people, the price of admission, the first barrier you need to cross, is literally getting over yourself. Politeness is court rituals where instead of hurting each other, we each hurt ourselves a tiny little bit. When we stop doing those rituals, we don’t stop hurting." – Randy, The NPC Question

Civility eliminates the constant mistrust and the endless war against all in a very simple way: to prove that you can be trusted, you open yourself up to being hurt first. You make a small sacrifice, on faith alone.

You open yourself up a bit. Doing this is not easy. It requires a complicated psychological maneuver. If you’re doing it to trick the other person, or for some personal gain, the highly attuned senses of the tribal man will pick up on your subterfuge immediately, and trust cannot be established. That is, you have to really believe in what you’re doing. You have to do it on faith alone, faith that you and the other can be friends. Faith that something other than warfare is possible.

In order to do this, you have to understand what you look like to the other. You have to be capable of introspection. What do I look like to another? To a person from the tribal world, you are, automatically, a threat. You are by default the enemy. You need to understand this perspective – you need to understand that you are something that creates fear in the other, that the other needs a way to understand you or to control you, to lock you down into something they can deal with. Logically, then, you have to show that you aren’t a big scary guy at all, but a person too – you have to open a hole in the armor, one they can easily see and exploit, and you have to do so willingly. They will see this, they will understand that you made yourself vulnerable on purpose, and to the logic of the tribal world it will make no sense.

The logic of the war against all is brute and inevitable. Anyone can work it out: there are limited resources, and so I must fight to get whatever I can. I must always be on guard. That is the only way to succeed. When you open yourself up, for no reason at all, it makes no logical sense. And it is precisely because it does not make sense that it works. You sidestep the logic with light, dancing feet; where the tribal man says, “I must take,” the civil man, the free man, says: “I will give.” The tribal man’s action is compelled by the heavy weight of his logic. The action of the civil man is freely chosen.

This requires bravery. You have to say, I am going to be the first to move. It’s no different than kissing a girl: you both want to, but someone has to be brave enough to move first. If you follow the logic of regular social interaction, the kiss will never happen, it is impossible. Someone must make a single motion, on faith alone, and suddenly – the impossible becomes possible.

This is what I couldn’t understand. When I was 16, I thought I was a social failure, but that was wrong. I was simply a coward.

Part 5: Freedom

When I call the philosophy of the true and the apparent world a slave philosophy, I mean that it is a psychology of those who are not free. It is a psychology that compels: the slave is driven by logical steps. Those steps go something like this: I have this small space, so does everyone else. To expand my space, I must take from the space of others; thus, my only gains can come from the losses of others, and likewise, others are always trying to gain from me. In order to keep what little I have, I must be suspicious; I must hold my cards to my chest; I cannot ever give anything away for free. I can trust no one. The loss of another is my victory, and therefore my great joy; what satisfies most is not to get ahead, but to take from others. What satisfies even more is to deprive: a step back for someone else is a step forward for me. If only I could deprive the master, he who has the most resources, who lives at the top, who can satisfy all his desires, who has all he wants, if only I could be ruler… I have the intelligence, in reality I am smarter and better than the master, but it is only these games we must play that hold me back… But wait! Now I understand! It only appears that way! Here is born the philosophy of the apparent world: It appears that I am weak, but in the true world I am strong, and if only I had my chance, if only I could take some more power, I would rule, I would be king, and I would make them all pay… And if I cannot have that, I will show them how everything they do is false. I will have my revenge.

Logic like this enforces itself. The slave uses this logic to at one and the same time justify his rage and resentment, and to make it impossible to act in a different way. It is fate, it is the logical outcome of the social system, of science, math, economics, it is Hobbesian, it is the will of the Gods, take your pick, you are not free.

Each step the slave takes is the brute but logical conclusion of the prior step. In this way his psychology demands nothing of him, only that he follow the war for resources to its ultimate conclusion. It only asks that he indulge his most base desires, for power, for space; it concludes for him that the world is empty, that there can never be any gains, that taking by force is the only virtue, that winning comes above all else, that trust and love cannot exist but are only appearance to hide the animality of our desires.

Civility, on the other hand, demands something of you. This is why we reject it again and again. Civility demands something difficult.

Civility requires a leap. It requires faith. It cannot be deduced; it cannot be reached logically. It has to be chosen at every step. In order for civility to work, you must believe that a different kind of world is possible. You have to believe this without any rational, logical reason to do so. Further, you have to frustrate your own desires, every animal instinct that tells you that all you can do is grab and take. Worst of all, civility has to start with you. There is no onboarding gift from civility that entices you to trust that it might be worthwhile. It appears, like Randy says, arbitrary and cruel. It hurts you – for civility, you must hurt yourself, you must give freely of yourself, you have to be the first to lay down you arms and to rescind your power. You have to show an open hand and say to all those hostile others “I believe, by faith alone, that we can be friends.”

I think there is something to be said for the fact that civility arises only out of the refinement of courtly Christian ethics into a social system, and that civility requires us to hurt ourselves instead of the other, and that the most famous and important act of Christ is that he not only hurt himself for all of us but gave up his very life: that his giving this gift to everyone else is the foundation of Christianity.

Christ gives up everything, he knows he is going to die. His followers do not understand, they plead for him not go, it makes no sense; Christ, like Abraham, smiles a weary smile; Christ weeps in the garden, because even he is unsure. Christ gives up everything, on faith alone, and the result is eternal life.

The slave is not free because he cannot choose; he can only react. Shame demands reaction, immediate and visceral, it must be resolved. The man who overcomes his shame becomes free. The slave is bound, fated to the world, to the logical necessity of the war against all; but the man who has overcome this logic, who has been brave enough to overcome this logic leaps above it on light, winged feet. He finds that he has opened up the wide and terrifying vista of freedom. Nothing anymore compels him. He alone is responsible for his actions, he rescinds the logic, he respectfully returns the ticket; he has become free.

I talked a lot about shame, but it wasn’t only that Freud was ashamed of his father. He was guilty that he was ashamed. This concept is so important that Cuddihy has an entire chapter elaborating on “the guilt of shame.” It is a particular kind of guilt, a unique sociological affect. The shame of the parent comes first, because you have stepped culturally beyond the parent. It comes on suddenly, triggered by the way they dress or talk, especially by how they speak; suddenly, you find, your parents embarrass you. Looking at your father, you no longer see the towering superman, but rather a backwards, archaic person, one that you have moved beyond. You see him, suddenly, as a normal person, a weak person. This is a universal experience, I contend, one experienced by every child as he grows up. Think of the young person speaking in disgust of the “backwards” views of the parent, the common talking point of the American thanksgiving family dinner – “my dad with his outdated, racist views…” You’ll see this discussion played out each year on twitter, around any major holiday, and many a great expression of disgust by the young for the people who raised them and the very environments they grew up in. Sam Hyde says that angry young men shouldn’t try to “redpill” their boomer parents. It will only lead to frustration.

The death of the parents in this way is an inevitable step of growing up. It is normal and healthy, I would say. If you revere someone you should not remain at their feet, for it would be a disservice – if you love someone, and they love you, they will want you to move beyond them, become more than they were, stand on their shoulders and see further. You should honor that. Being ashamed of them for their backwardness is the consequence of moving on. It is inevitable. Being guilty about that – being guilty about your shame – is also part of that problem. The difference with the guilt is, you get to choose how you deal with it.

Freud is ashamed of his father, deeply ashamed. This deep shame engenders an equally deep guilt of his shame. His own father, who raised him and held his hand and loved him, could only be seen by Freud as impotent and weak. Freud commits a parricide of his father, abandons him in the backwards darkness of the shtetl. But he feels guilty, terribly guilty about this. The guilt doesn’t go away. So he invents psychoanalysis – it is not my particular desire to kill my father, it is the universal desire of all people, hidden in the unconscious. He takes his particular, personal guilt and mutates it into a universal psychological problem. Instead of confronting his guilt, he says that actually, everyone secretly wants to kill their father; in the apparent world you love your parents, but in the true world, you are all like this, you are all as low down as me. He transforms his particular problem into a universal scientific problem. He does this because he is a coward.

When Sophocles wrote Oedipus Tyrranos, he was writing for a demo of Athenians who wanted anything but responsibility. A plague had come to Athens, a horrible war had ruined them; all concepts of honor and bravery had after long years of grueling war disappeared, and men did what they once did in privacy and shame openly in the street. The Athenians wished more than anything that all this was someone else’s fault, that all the horror of the world was not theirs to bear. But it was. Sophocles knew this, and he knew that if this train of thought were to continue it would be the end of freedom. Not political freedom, but psychological; he knew how the Athenians wanted to see the plague. It had killed a quarter of the population of the city, all in a few months. It was random, unjust, unfair. Their very best men, men like Pericles, had died not in battle, but had been killed by the random cruelty of the world, and there had been nothing, absolutely nothing, they could do to stop it. Death was inevitable; the Athenians turned to pessimism. They believed – wanted to believe – that there was nothing they could do anymore.

Sophocles, however, understood the psychological maneuver they were pulling. He realized that his once brave Athenians were about to invent philosophy. So he introduces a plague into his play, right at the very start, just like the one in real life, and he gives the Athenians a million leads as to why the plague struck Thebes. His goal was that the plague was anything, anything but random, be it brought on by the Spartans as a bioweapon, or by the anger of the Gods, it didn’t matter what reason they believed. Because if there was a reason, then it wasn’t fate like the Athenians wanted, it wasn’t the logical end of a long series of inevitable logical steps. The Athenians wanted it to be inevitable, they wanted the responsibility, and the guilt of responsibility, to go away, the plague was only the proof they would use to obliterate responsibility; they invented all sorts of reasoning, all sorts of philosophies that made things not their fault. But it was their fault.

Sophocles was going to save them from themselves. If he could prove the plague wasn’t random – that it was not inevitable – then things could still be affected by their actions, then the end of all that was good in the world was not an inevitable logical conclusion. He needed to show them – remind them, for they had once believed this – that men were free, holy, divine, divine because they could act, because that meant that they not only were granted that limitless, terrifying freedom, that infinite power that man possess – they also had a duty, an absolute ethical duty, to act, because then the fate of the world was up to them. If Sophocles was right, then it had always been up to them. They had to stop reacting to the world; they had to choose. The waters were cleared, there was no longer any question. Freedom is guilt: guilt means you are at fault, but guilt can be atoned for by action.

Freud was ashamed, he was guilty at his shame, so he turned his personal guilt into an inevitable sexual logical process and then projected it on the entirety of the world, because he was a coward. A real man would not take his guilt and try to disperse it – a real man would act. A real man would hear the sentence: “your father is impotent, your father is from a backwards land, forever will he blight you – you have crawled up from the mud and dirt! Worm that you are, you think we cannot smell the earthy soil on you? No matter how much you wash you will not be free of the scent!” Would hear this pronouncement, and would not despair, for his action would be immediately available: he would turn to his father, this prodigal son, he would weep, he would embrace him: he would choose to forgive. And then he would be free.

Like making yourself vulnerable, forgiving must be done freely, on faith alone. It comes at no gain to yourself. It makes no sense. It has to be chosen, freely.

When I finally gave up on my teenage vulgarity, and decided to start acting like a person, I found that all those “scripts” people spoke in, all the “fakeness” that I bemoaned as a teenager was not fake at all, but only an avenue for opening up to another person. I found that by listening closely and giving up a little bit of myself at a time, I could easily make deep and meaningful friendships. I discovered all these people I thought were so fake were real people after all, full of interest and genius and life, that every one of them was worth listening to. I don’t want to get too sappy about it. I don’t want you to take from this essay some pablum like “everyone is wonderful if you just open up!” because they aren’t. But you would be surprised at how many are. I am surprised every day.

I found in those days that to my enormous surprise there was nothing wrong with me at all. I could talk to girls after all; some of them even thought I was handsome and funny. The social lock I had felt, the distance between my private space and the Others private space, could be bridged with ease in public space, with civility. But it had to start with me. I had to take responsibility for my failures instead of projecting them onto the world. I had to be brave, and I had to act, on faith alone. No logic could save me. And when I finally did act – when I took that tiny, little step of bravery by making myself vulnerable – it worked. It was, and continues to be, astonishing how well it worked. It is a kind of miracle. The fountain never dries. Eternal life.

I am reminded of something Pericles said in his famous funeral oration. Indulge me one more long quotation. Pericles is speaking here of the bravery of the Athenian dead, but far more importantly, he is speaking to the living.

“So died these men as became Athenians. You, their survivors, must determine to have as unaltering a resolution in the field, though you may pray that it may have a happier outcome. And not contented with ideas derived only from words of the advantages which are bound up with the defense of your country, though these would furnish a valuable text to a speaker even before an audience so alive to them as the present, you must yourselves realize the power of Athens, and feed your eyes upon her from day to day, till love of her fills your hearts; and then when all her greatness shall break upon you, you must reflect that it was by courage, sense of duty, and a keen feeling of honor in action that men were enabled to win all this, and that no personal failure in an enterprise could make them consent to deprive their country of their valor, but they laid it at her feet as the most glorious contribution that they could offer. […] These take as your model, and judging happiness to be the fruit of freedom and freedom of valor, never decline the dangers of war.”

The whole thing is important, but I would like to point to the last sentence in particular. Happiness is the fruit of freedom, and freedom is the fruit of valor – of bravery. Note that it’s a Venn diagram. Bravery comes first, then freedom, and then, finally, happiness. We are going to have to be brave.

Otherwise good essay, but Plato describes a better kind of city because, at the time, it was actually possible to found new cities, or to convince the tyrant of one to follow your ideas. He invents the genre of the utopia because he believed he could make something resembling it in the real world (the utopia resurfaces as a genre, in Italy, in the early 16th century, for a reason...). Read 'Laws', not Nietzsche's ordeal of civility with the philosophical tradition, if you want to know what Plato thought.

Great essay and especially a great analysis on Freud. About 3/4 into it I got confused as to where all the talk of "faith, not logic" was suddenly coming from. Game theory is logical, I kept saying to myself, and under certain conditions civility is the game-theoretical optimal move. I think if you were not trying to force it to point to Christianity, you would agree that civility is a remarkable phenomenon and important step in human advancement, but is not like, metaphysically sacred